I had a great trip to Dubai and Abu Dhabi, I enjoyed the conference there and even more so, the meetings I had with a number of senior HR people, in banking and other sectors.

I had a great trip to Dubai and Abu Dhabi, I enjoyed the conference there and even more so, the meetings I had with a number of senior HR people, in banking and other sectors.

The UAE is a hugely dynamic place, and that presents HR practitioners and their organisations there, with a war for talent that in many ways is just as challenging as that in China.

Before my trip, I had prepared myself by reading Aamir Rehman's book, Dubai & Co. Rehman points out 5 deadly misconceptions about the UAE:

- It’s all about oil. Well I didn’t even get to meet anyone from this sector – banking, construction and other industries are clearly thriving too.

- Everybody’s rich. The Emirates are clearly very prosperous, but there is a huge amount of poverty there as well – and this is clearly on show around most building works.

- The GCC customer ‘hates us’. I’m not too sure what Rehman really meant by this but I found a very high degree of respect between all the cultures present and was very pleasantly treated by all the locals and expats that I met. A few people did refer to some discrimination though.

- Women don’t matter. Women are an increasingly important customer and source of employment (see the Economist’s recent article on this).

- The markets are entirely Arabic. As well as locals, there are a large number of Arab expats from Egypt, Lebanon, Yemen and elsewhere, but also Asians from the Philippines and the Indian sub-continent, and of course, Europeans, Americans and Australians.

There is, however, an interesting divide between locals who control the bulk of the wealth and resources, and expats who are clearly ‘hired help’. I guess this is often the case, it just seems more so in the UAE – perhaps because expats make up 99% of employees in the private sector.

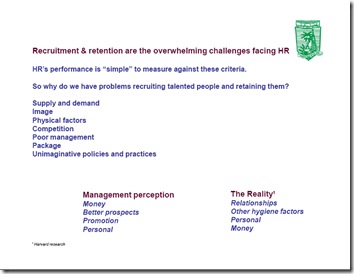

Rehman provides the attached slide to demonstrate the benefits of both employment groups.

Because of the need to retain this balance, and at least in banking, where due to a requirement to increase the percentage of the workforce that consists of Emirate citizens by 4% per year, the recruitment of nationals is a very major focus, these individuals need to be managed as a separate talent group.

Meeting targets for nationalising the workforce is a particular challenge given that the local education system are still not providing the quality of local employees that businesses require (I’ve previously posted on this problem in China too).

This is supported by McKinsey’s 2007 article on Gulf Labour Policy which questions whether local education systems across of the Gulf Co-operation Council states (GCC) prepares people for professional employment: “About 90 percent of first-year students at UAE University require one year or more of courses in basic math and literacy.”

In addition, introducing the International Journal of Human Resource Management’s 2007 edition on the Middle East, Budhwar and Mellahi state that while GCC and other Middle East countries have invested heavily in developing their human resources: “Despite these considerable investments, the output of the education system is less than expected and it is experiencing difficulty in meeting the demands of the labour market in terms of both quantity and quality of skills. It seems that, so far, the emphasis has been put primarily on human resource development rather than the utilisation of acquired skills and knowledge.”

However, I think this is less of an issue in the UAE than elsewhere in the GCC, and certainly seems to be a minor concern in Dubai where there are a couple of excellent academic institutions as well as other major investments in learning such as Dubai's Knowledge Village.

Certainly, the nationals I met at the conference and in my business meetings were all extremely knowledgeable and professional (the questions speakers were asked during the conference I was chairing were some of the sharpest I’ve heard at conferences recently).

However, in general, and as found elsewhere, forced positive discrimination seems to have failed to work successfully. So organisations end up arranging for their expat workers to be employed by other organisations, taking them off their official workforce and therefore reducing the target for the employment of nationals that they’ve been set. Others put nationals on the payroll who they wouldn’t otherwise employ, and expect little from them in the way of productivity or contribution.

As McKinsey note: “A quarter of national employees fail to show up for work regularly, while many leave jobs just six or nine months after taking them, citing boredom of a lack of interest. Some companies even choose to pay low-performing employees simply to meet the quote but ask them to stay at home.”

This situation has led to a decrease in trust and the creation of negative stereotypes of UAE nationals.

In an Arabian Business article earlier this month, Jassim Ahmed Al Ali of the Human Resources Department of Dubai Municipality was quoted as stating:

"As much as 10 per cent UAE nationals resign their jobs per annum due to social and cultural factors because low-trust is an impediment to employment for UAE nationals. This is in addition to gender inequality in terms of position and salary. Nepotism, or what is called locally as wasta, also prevails in the workforce".

Al Ali suggests that trust can be redeveloped by “treating UAE national employees fairly, justly and consistently, and their participation in decision-making, acting on their creative suggestions, giving them feedback on performance, empowerment and recognition”.

"To address gender inequality, Al Ali said policies and legislation should be enacted to ensure the representation and participation of UAE women in management positions. The labour law, he said, prohibits gender-based discrimination in terms of salary packages and career development opportunities. "However, this must be monitored to ensure that organisations adhere to them in practice," said Al Ali.

With regard to nepotism, Al Ali suggested encouraging the use of systematic criteria in employee selection such as psychometric, learning and aptitude test, and establishing an arbitration commission with the powers to investigate and manage complaints of nepotism, including demanding evidence of transparent recruitment and promotion practices from all employers.

This organisation also undertakes awareness campaigns to alert citizens against nepotism, and publishes proven nepotism incidents and their outcomes. The paper also identified an open-door communication policy and measures to reinforce and retain their talented employees as the best organisational culture that will attract UAE nationals.”

At the conference, Hani Hirzallah from Barclays presented their approach to emiritisation. Within banking, there are 60 banks employing 30,000 people of which just 5,000 are UAE nationals. So Barclays can keep track of these people, and have a good understanding of their performance and likely commitment if they apply.

I thought this was a great approach, although I wondered, if it would also provide a basis for a more proactive approach eg head farming.

We also had a very interesting debate on remuneration. In general it seemed that employers do offer higher salaries to local employees in order to recruit and retain them, although there seemed to be a lot of discomfort in doing this and worry about the tension this creates.

I was slightly surprised by this, as different salary scales are a common aspect of reward in locations with a heavy expat presence, although more commonly favouring the expat rather than the local as seemed to be the case here.

For example, when I was an HRD in Russia, our salaries for expats were approximately double that of Russian locals, with Russian returnees, employees of mixed parentage etc being paid somewhere between the two. I think this division was fairly widely understood and if not liked by our Russian staff was accepted as something that needed to be done.

And I was also surprised at the lack of agreement between participants about whether this was something they needed to do – which indicates an immature reward structure in the UAE.

The prevailing thinking that local salaries need to be higher than for expats also seems at odds with local reward surveys. For example, Mercer’s report, Managing ther UAE's HR Environment, finds variations from a 5% difference in favour of expatriate senior managers to as much as 80% difference in favour of expatriate professionals. Expat workers are paid a premium for their experience, to cover their relocation costs and due to the high cost of rented accommodation and hotels in Dubai.

I think one reason for this disparity is that there is a need to distinguish between different types of expat and the different roles they work in. As McKinsey’s article points out, the UAE has a high proportion of expats of workers from countries such as Egypt, India and the Philippines who work at wage levels much lower than UAE nationals would accept, often in sectors that nationals have traditionally shunned, such as construction and manufacturing. Other expats work in professional roles doing work there are not enough skilled nationals to fulfil.

Mercer’s report also notes that “another discernable trend in response to salary inflation is that companies are now focusing more strongly on the total rewards concept. Bonuses and performance-related pay now represent a higher proportion of the average reward package than previously”.

Dubai Municipality’s Al Ali suggests that “there is a need to introduce a pay-scale better than the current market rates to satisfy UAE nationals. For this, the type of remuneration that attracts them should be identified. There is also a need to introduce programmes that propel UAE nationals as the employers' first choice.”

I think many UAE employers are already responding to this requirement, and many are offering significantly reduced and very flexible working arrangements in order to make employment look attractive. But the key, as Al Ali notes must be to create a “commitment-based work culture, instead of relying heavily on monetary rewards and top-down mechanisms to try and combat job-hopping”.

Of course, one of the things that attracts me to the UAE is its rapidly maturing consultancy market. As Management Consultant International pointed out recently:

“The last three years have brought rapid change to the Middle East consulting market. A rapid maturation of clients, healthy economic drivers, and the entrance of a plethora of new consulting firms are intensifying competition and helping to educate and drive the market further forward. The result is an opportunity for quick growth for consultancies with the right business models and go-to-market approaches.” And Arthur D. Little are quoted as saying: “The growth will be purely based on how many quality people we can recruit. If the firm has 100 people, it can get projects to keep those 100 people busy. If there are fewer people there will be fewer projects. So if we get good people, we hire. That’s what’s happening now.”

This is what real talent management’s about!

Hello to everyone I met at today's Learning & Skills Group conferencette. I hope you'll get time to take my social connecting / web 2.0 survey (top right-hand corner of my blog).

Hello to everyone I met at today's Learning & Skills Group conferencette. I hope you'll get time to take my social connecting / web 2.0 survey (top right-hand corner of my blog).